February 2011 issue

Click on link to view Intercom February contents

Editorial and Newsletter resources

Feature Article

Mark’s Gospel and Recovery for Battered Believers (pdf)

Professor Séamus O’Connell

Mark’s Gospel and Recovery for Battered Believers

Séamus O’Connell introduces some key themes from the Gospel of Mark which we read in our Sunday celebrations this year

The Gospel of Mark, like each of the four Gospels, is a story of hope. But Mark’s is a story which is no easy read. The Gospel of Mark was sidelined within the Tradition, not only because Matthew, Luke and John are fuller, but because Matthew, Luke and especially John are less threatening, and less disturbing. A risen Jesus who reassures his disciples that he ‘will be with [them] always until the end of time’ (Matt 28:20) or who is ‘the Way, the Truth and the Life and that nobody will come to the Father, except through’ him (John 14:6) is far more attractive and consoling than a Jesus who dies crying out on the cross, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’ (15:34; Passion Sunday)[i] This is Mark’s disturbing Jesus; he is a long way from the Jesus of John who can expire with the consolation that ‘it is accomplished.’ (John 19:30) That such a powerful healer and teacher would accept his own persecution and suffering—suffering at the hands of men—as the will of God, is ‘the Christological surprise of Mark’s Gospel’.[ii] Mark is written for people of faith who are battered by what life has thrown at them; it is written for people who feel that the Lord is passing them by (Mark 6:48; cf. Exod 33:17–23). It is written to bring what Jesus brought—the good news of God (1:14)—namely, that God has not dispersed the darkness with some divine magic, but that God and God’s power are to be discovered for those who, like Jesus and a myriad of other characters in Mark, leave all, only to be cast into a darkness to discover in and through that who God really is and what God is really about.

This way is not an easy way; it was not an easy way for Jesus, it was not an easy way for his disciples, it certainly is not an easy way for any disciple today. This way was not easy for Jesus; have a look at the constant stream of conflicts that envelop his ministry—conflicts with religious authorities, conflicts with his own disciples and, in the end, even conflict with God.

This way was no easy for the disciples. Peter and Andrew, James and John follow Jesus leave everything to follow Jesus (1:18, 20; 10:28). However, as the story progresses, they show a deep resistance to parting with their own funds,[iii] display rampant self-interest and ambition,[iv] are clearly exclusive,[v] evidence a profound lack of self-knowledge,[vi] and a stark lack of courage.[vii]

These fallible disciples are in stark contrast to a slew of ‘minor characters’ who model ideal responses to what God is doing in Jesus and his ministry: the poor widow whose two cent—all she had (12:44)—are given to the Temple and thus to God (12:42–44; Sunday 32), the woman who anoints Jesus to the chagrin of those who have designs on her extravagant gift (of 300 denarii—about €30,000 in today’s terms) but earns his protection and praise because she did all she could (14:8; Passion Sunday). There’s Bartimaeus who asks to see again and who persists in his request until his sight is restored … and then follows Jesus ‘on the way’. (10:52; Sunday 30)

These ‘minor characters’ are not Jesus’ disciples! They appear in the story; we glimpse their generosity, their radicalness, their faith. They provide a snapshot of a world in which the goals of discipleship take flesh: in courage, openness, humility, and total dedication. In short, all the things the disciples do not display—but disciples they are not!

The real disciples of Mark, like their master, are confronted with danger and death. In Jesus’ hour of need, they run away; even Peter, who returns to follow at a distance (14:54), denies and finally curses his master when attention is turned to him. But, in contrast to the wonderful minor characters, the disastrous disciples endure (13:13) with Jesus (cf. 3:14) … and he endures with them (16:7; Easter Vigil).

To read Mark well, we need to bear in mind that those who became the great apostles began their journey of discipleship as very compromised and very fallible individuals. This is the good news of Mark. Amazing disciples begin as profoundly fallible disciples. Indeed, without the discovery of our own weakness, blindness, self-interest, one cannot welcome the Gospel of God. Without that painful discovery, one lives a profound illusion. Without recognizing the consequences of our blindness and the concomitant need for forgiveness, disciples will never be empowered to walk It is surely significant that, in the Story of the Paralytic (2:1–12; Sunday 7) the narrative order has faith, forgiveness, conflict and then the walking. For Mark, conflict and healing go hand-in-hand. Without the conflict, the paralytic would never have walked!

Mark wrote his story of Jesus, God and the community of disciples for people who were tired of the silly and shallow caricatures that pass for faith. It is written for women and men who see and taste the darkness by one who knows that, in that darkness is a fragile but enduring dawn. Do the dark powers get their man? Absolutely! Those who set out to destroy Jesus win the day; this is how their plot is described in 3:6 (Sunday 9). They succeed in having him utterly and totally smashed, just like the woman’s jar is smashed in 14:3 (Passion Sunday). But do they destroy him? How you answer that question is the key to your reading of Mark… and of life. The hope that Mark offers is not these things will not happen, rather Mark’s promise is that when these things happen, God is very near (13:29; Sunday 33). Mark proclaims that God is alive, at work during the night and in the day, we know not how (see 4:27). He calls us in the night and in the day to recognise the work of God and to abandon ourselves to it. He calls us to follow the one who is still crying in the desert (1:3; cf. 15:35) and who will always go before us to Galilee (see 16:7; Easter Vigil).

Séamus O’Connell

Professor of Sacred Scripture

St Patrick’s College

Maynooth

[i] All references, unless otherwise indicated, are to the Gospel of Mark.

[ii] Elizabeth Struthers Malbon, Mark’s Jesus (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2009), 204.

[iii] ‘Shall we go and buy two hundred denarii worth of bread, and give it to them [i.e., the crowds who have followed Jesus into the desert] to eat?’ (6:37)

[iv] James and John come to him in secret and ask to ‘sit, one at your right and one at [your] left, in your glory’. (10:37; Sunday 29)

[v] ‘We saw someone casting out demons in your name, and we forbade him, because he was not following us’. Jesus does not take the same stance: ‘Do not forbid him; for no one who does a deed of power in my name will be able soon after to speak evil of me. For the one that is not against us is for us.’ (9:38-39; Sunday 26)

[vi] ‘Peter says to Jesus, “Even if they all fall away, I will not.” And Jesus says to him, “Amen, I say to you, this very night, before the cock crows twice, you will deny me three times.” And Peter replies vehemently, “If I must die with you, I will not deny you.”’ (14:29–31) Of course, Peter runs away, and even when he follows from a distance, when challenged he repeatedly denies Jesus. (14:68–71; Passion Sunday)

[vii] See Peter’s denials in 14:68–71 (Passion Sunday).

To view the article in pdf format, click here.

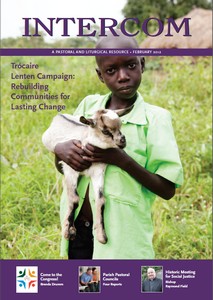

Intercom

Intercom is a pastoral and liturgical resource magazine published by Veritas, an agency of the Irish Catholic Bishops Commission on Communications.

There are ten issues per year, including double issues for July-August and December-January.

For information on subscribing to Intercom, please contact Ross Delmar (Membership Secretary):

Tel: +353 (0)1 878 8177 Email: [email protected]