June 2015 issue

June 2015 issue

Click on link to view Intercom June contents

Editorial and Newsletter resources

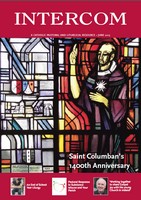

Feature Articles National Celebration of the 1400th Anniversary of the death of Saint Columban (pdf)

Bonus online content: Saint Columbanus Prayer Service

Spirituality of Saint Columban

Fr Tommy Murphy SSC

A strong desire for union with God was the driving force in the life of St Columban. He believed that the risen Christ was present in him and the world around him: and that Christ was the source of all the gifts he needed in life. St Columban was heavily influenced by the spirituality of the Desert Fathers. They were determined not to succumb to the seductions of the secular world around them and committed themselves to the search for their true selves in the deserts of the Middle East. In Ireland we do not have deserts but we do have plenty of quiet lonely places which the Irish monks sought out. There are over 200 places in Ireland named Dysart (desert) which gives some indication of how widespread was the practice among early Irish monks of seeking out quiet places of solitude. Solitude and silence were the prerequisites for this inner search which was driven by the belief that God dwelt at the deep core of their real selves.

The Lives of St Anthony of Egypt and St Martin of Tours were well known in the Irish monasteries of the 5th and 6th centuries. The writings of St John Cassian were also standard documents in Irish monastic libraries. These books contained the wisdom of the Abbots from the desert which outlined the strict ascetic practices and prayer methods to be followed by those who sought the way to union with God in the heart of their true selves. The ‘Cave’ is a strong motif running through the life of St Columban: from his early foundation in Eastern France to his final foundation in Bobbio we find that he regularly left his monastic community to spend time at prayer in caves some distance from his monastery. He was a man dedicated to long periods of private and communal prayer. This commitment to periods of silent solitary meditation is reminiscent of Jesus’s own prayer pattern which was rigorously practiced by the desert monks. Here in the silence of his own heart Columban came in contact with the presence of God deep within him. The results of these times of deep communion with God are evident in his writings: in particular his Sermon 12 and 13 are among some of the most mystical writings we have of any European monk. In Sermon 13 he writes: ‘how lovely is the fountain of living water, whose water fails not, springing up to eternal life. O Lord, you yourself are that Fountain ever and again to be desired, though ever and again to be imbibed. Ever give us, Lord Christ, this water, that it may be in us too a Fountain of water that lives and springs up to eternal life.’

How to keep alive the awareness of their close relationship with Christ was the major priority of their spiritual life: the carrying of the sacred host in a Pyx hung around the neck of each monk was a sign of this ongoing close connection with the risen Christ. The regular cycle of prayer, work and study ensured that their focus on their friendship with God was never far from their minds.

Saint Columban saw nature as his teacher about God. He encouraged his monks to look at the magnificent works of creation all round them in order to understand the nature of God. This link between his appreciation of the awesomeness of nature and his strong belief in God comes out strongly in his early sermons.

There was a pastoral and caring side to Columban which contrasts with the harsh and overly ascetic image that initially comes across from his writings. His Fourth Letter written to the members of his Luxeuil Community as he awaited deportation back to Ireland at the port of Nantes, offers us a rare but sincere insight into his caring attitude for his fellow monks. It also offers us a glimpse into the personal angst he endured as he exercised leadership in the same community. His pastoral sensitivity is evident in his rules for clergy and laity living outside the monastery. At that time in Western Christianity his introduction of private confession and penance was a welcome relief to many Christians in several parts of Europe.

His whole life was inspired by his belief that only God alone could answer the deep thirst in his heart. In Sermon 12 we glimpse something of this fundamental stance where he writes: ‘Lord grant me I pray in the name of Jesus Christ your Son, my God that Love which knows no fall, so that my lamp may feel the kindling touch and know no quenching, may burn for me and for others give light. Grant us Christ, to kindle our lamps ……that they may shine continually……and receive perpetual light from You, The perpetual light, so that our darkness may be enlightened, and the world’s darkness may be driven from us.’

Intercom

Intercom is a pastoral and liturgical resource magazine published by Veritas, an agency of the Irish Catholic Bishops Commission on Communications.

There are ten issues per year, including double issues for July-August and December-January.

For information on subscribing to Intercom, please contact Ross Delmar (Membership Secretary):

Tel: +353 (0)1 878 8177 Email: [email protected], or click here to subscribe online.